Culinary Cultural Heritage

According to the UNESCO Convention on Safeguarding Intangible Cultural Heritage, adopted in Paris in 2003, intangible cultural heritage refers to uses, representation, expressions, knowledge and techniques, which communities recognize as part of their identity. It is transmitted from generation to generation, constantly recreating itself for groups as a function of its surroundings, interacting with nature and its history. For UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage is at the same time traditional and contemporary…it constitutes living heritage.

Safeguarding intangible heritage is important in the measure that it promotes respect for cultural diversity, human creativity, strengthens identity and continuity, and contributes to social cohesion.

According to this convention, five contexts exist which comprise this type of heritage. One of them refers to knowledge and uses related to nature and the universe, which includes a series of wisdom, techniques, competences, practices and representations, that communities have created in their interaction with the natural environment. Corresponding to this context, among others, is gastronomy, as it reflects the enormous diversity of knowledge, habits, products and beliefs, which are the result of human creativity.

In this context, an important action and safeguard is the creation of a tourist product, which includes the creation of a mills and bakery route and the continued support for the Bread Festival, initiated by the Sisters of the Order of Our Lady of the Conception Museum. This route not only seeks to recover Cuenca’s old recipes of traditional bread making for the enjoyment of locals and tourists, it also seeks to contribute to neighborhood solidarity and to strengthening the city’s cultural identity. In Cuenca, craft occupations have played a fundamental role from the moment of its founding and are reflected today in the urban physiognomy.

The History Of Gristmills And Bread-Making In Cuenca

The arrival of wheat to what is now Ecuador in the decade of the 30s of the 16th century is attributed to Brother Jodoco Ricke, a Franciscan, who five years later was also in the area of the Cañaris.

Soon after that, wheat was grown above all the areas of Cañar. These landowners, just as the gristmill owners, became known in Cuenca as wheat lords and gristmill lords.

This early cultivation also explains why just a few years later the first gristmill was installed in the future town before it was founded in 1557. The owner was Rodrigo Nuñez de Bonilla, an agent of the crown and miller who arrived from Quito.

Milling grain in the town of Cuenca during the colonial period was done along a section of the left bank of the Tomebamba River, especially in two areas: Todos Santos and El Vado. This situation would last until the beginning of the 20th century.

Making bread with wheat flour began at the same time as the beginnings of the colonial city of Cuenca. In this atmosphere and in these times, it is presumed that the first establishments for making bread were in homes, without persons identifying themselves as bakers. In any event, from the first third of the 17th century, the first stores that sold bread exclusively appeared in the Todos Santos area. Not in vain did this semi-urban section become known for the city´s gristmills.

At times, it is possible to know certain details with respect to the tools that were involved in bread making. Many of these tools were available in homes, for example: troughs, planks to set out bread, baskets to carry bread to the market for sale and sieves with their troughs for sifting flour. There is also data about the type of foodstuffs that were prepared for sale, as in the case of the Indian women who prepared alfajores and “rosquetas” in the convent of the Conceptas in the second decade of the 17th century under the watchful eye of Sister Doña Santa Lucia, a member of this bread community.

These goodies were given to an intermediary, Diego Diez Franco, for him to sell. In any event the importance of bread was such that in the 18th century, a bread market, known as Tandacatu, had formed just to the east of San Sebastian.

The 19th century better illustrates this branch of food crafts. On the one hand, there are references to persons who can be perfectly identified by their work. In any event, it appears to be a constant that women would perform this function, a situation which would not become the exception in Cuenca until the beginnings of the 19th century, when men came to be included.

In addition, it is noteworthy that during this period, craftsmen in bread-making in Cuenca did not associate themselves, for example, in a professional guild, such as occurred in the nearby city of Azogues. At the close of the last century bakers requested that rules be drafted for their activity, a clear demonstration of how they came to identify themselves, as well as a demonstration of their self-esteem.

All during their history, female and male bakers of Cuenca have firmly established their presence in different ways, especially in the traditional quarters of the city: Todos los Santos and El Vado, giving rise to certain chronicles. And in the sphere of local music, Cuenca’s bakers have merited songs dedicated to them.

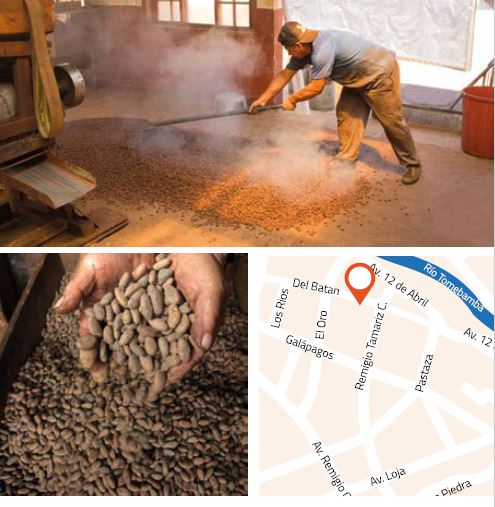

“Fátima Industries” Chocolate Mill

The family business of Fatima Industries offers the possibility to discover the traditional process to obtain one of the products most desired by locals and foreigners alike: pure dark chocolate, the base for preparing innumerable exquisite recipes.

Catalina Peralta, the daughter of Luis Honorato Peralta, now manages her deceased father’s business. She explains that cacao is obtained from different places on the coast, such as Machala, La Troncal and Manabi. The first step in the process is selecting the beans, choosing only the best quality. Then the beans are roasted, crushed and winnowed in order to completely remove the husks. Finally, the pieces of bean are ground to obtain the prized liquid, which after cooling is poured into molds or onto “achira” leaves (a large-leafed plant of the cannaceae family), depending on the desired presentation of the final product.

Fatima Industries’ chocolate is 100% natural and is sold in different markets, stores and supermarkets of the region. In addition to discovering a close up view of all the processes for making chocolate, tourists who visit the factory can sample it and confirm its delicious flavor and aroma.

[color-box color=”gray”]Address: El Batan 4-56 between El Oro and Remigio Tamariz

Telephone: 288-0109 / 099-071-8782

Hours: Monday to Friday from 9h00 to 16h00 (preferably with a prior appointment)

Price of the visit: $3.00 USD per person (includes sampling)[/color-box]

Todos Santos Heritage Complex

The Oblate Sisters have played a fundamental role in the history of the Todos Santos quarter of the city. In their desire to obtain resources to educate the children in their care, they dedicated themselves to baking, among other work, developing an authentic culinary legacy that today is part of the identity of this quarter. In fact, some of the bakers of the quarter learned the trade after having worked for the sisters making bread.

The bakery is now open to the public, and visitors can discover the secrets to preparing the Cuencanos’ authentic bread and exquisite traditional sweets, such as quesadillas, alfajores, truffles and cookies. Also part of the Heritage Complex are the “Gastro Todosantos” restaurant, an art gallery, a river overlook, an event hall and the “Puro Café” coffee shop. There are also guided tours of these areas.

[color-box color=”gray”]Address: Calle Larga y Vargas Machuca

Telephone: 2839100

Hours: Tuesday to Saturday from 8h30 to 17h00

Price of the visit: 0.50 USD for children / 1.50 USD for students / 2 USD for adults and foreign visitors[/color-box]

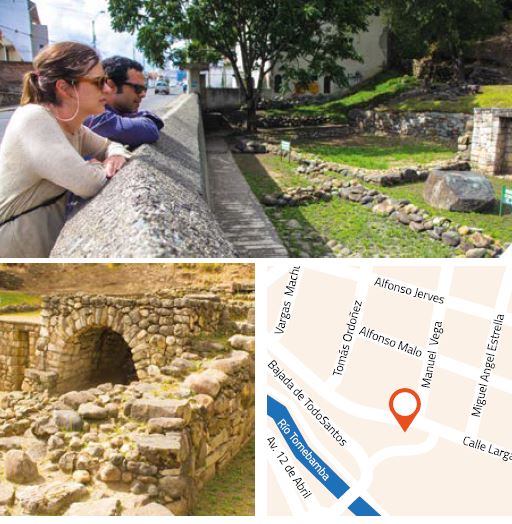

The Todos Santos Gristmills (Manuel Agustin Landivar Museum)

On the site corresponding to the Todos Santos archaeological complex, the Spaniard Rodrigo Nuñez de Bonilla, one of the first to arrive in these territories, constructed a gristmill in the year 1536 to process wheat. The mill’s structure consisted of

Later, other gristmills were constructed in the same place, which from 1600 became the property of the Sisters of the Immaculate Conception. Their administrator, Presbyter Martin Marchan, constructed for them a chamber with a drive wheel, which was installed in a room with a wide half-barrel vault.

The canal that fed water to the gristmills was definitively suspended in 1929 to permit construction of the sewage system for Calle Larga. Consequently, the gristmills were closed and remained forgotten for a long time until 1972, when the Estrella family discovered the archaeological site while excavating for the foundations of a home. Now this site is under the administration of the Azuay Branch of the Ecuadorian House of Culture, through the Manuel Agustin Landívar Museum.

[color-box color=”gray”]Address: Calle Larga and Manuel Vega

Telephones: 282-1177 / 099-552-0186

Hours: Tuesday to Friday from 10h00 to 18h30 and Saturdays from 10h00 to 14h00.

Price of the visit: Admission is free.[/color-box]

The “Todos Santos” Traditional Bakery

Augusto Tenemasa, proprietor of the business, explains that traditional recipes are used to this day because clients request them the most. Although flour comes prepared by different industrial mills, chemical ingredients that can be prejudicial to health are excluded from the bread’s preparation.

A few meters from this locale one finds small businesses, which delight tourists and locals with traditional delicacies they still prepare, such as “Chilean apple” jelly, figs in syrup, humitas and ground corn or corn flour tortillas.

[color-box color=”gray”]Address: Mariano Cueva 4-101 between Honorato Vazquez and Calle Larga.

Telephone: 282-5989

Hours: Monday to Saturday from 7h00 to 20h30.

Price of the visit: A voluntary contribution is suggested.[/color-box]

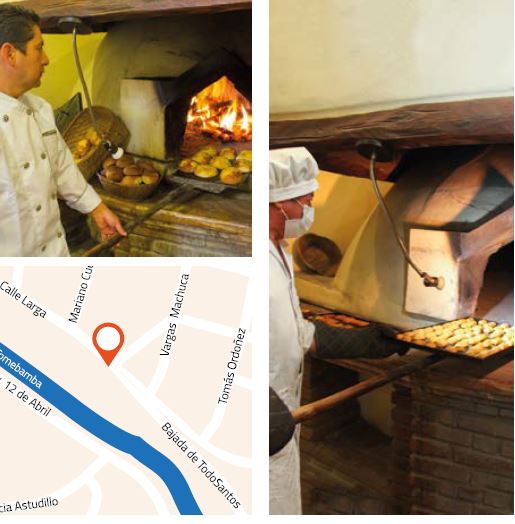

“Traditional Wood-Fired Oven Bread” Bakery

The bakery has one of the oldest wood-fired ovens of the city, which has a base of 1.3 meters, constructed in the following manner:

- A layer of iron of 10cm

- A layer of cattle bones of 30cm

- A layer of broken glass of 30cm

- A layer of rock salt of 20cm

- A layer of bricks

The oven is heated to a temperature of 180 degrees centigrade using eucalyptus wood. Small bread rolls take 15 to 20 minutes to bake, while large loaves require approximately 40 minutes. Traditional recipes are used to make cholas, gusanitos de queso, rositas de huevo, mestizos, costras, corn bread, and shortening cookies, among others.

[color-box color=”gray”]Address: Mariano Cueva 4-90 between Honorato Vazquez and Calle Larga

Telephone: 282-6173

Hours: Monday to Saturday from 7h00 to 20h30.

Price of the visit: A voluntary contribution is suggested.[/color-box]

The Mentidero Bakery

The Mentidero Bakery

Using ingredients of the highest quality, this bakery makes a delicious bread with Argentine recipes. The traditional Cuencano touch comes from the wood-fired oven, whose design is based on local construction techniques that employ materials such as adobe, refractory brick, rock salt, sand, bone, steel and glass.

Visitors to the bakery have the opportunity to observe the process by which delicious recipes are prepared, such as Argentine peasant bread, flavored bread, focaccias, empanadas, apple crumble, etc. In addition, one can sample bread recently taken from the oven with delicious organic coffee from Loja. Complements to this establishment are the “Marea” pizza parlor that functions at night, plus occasional cooking classes, tastings and culinary discussions. Tourists and families can assemble and bake their own pizzas on Sundays.

[color-box color=”gray”]Address: Hermano Miguel 4-79 and Honorato Vazquez

Telephone: 282-7827 Ext. 102

Hours: Monday to Friday from 8h00 to 15h00 and from 16h00 to 1800; Saturdays and Sundays from 8h00 to 15h00

Price of the visit:A voluntary contribution is suggested.[/color-box]

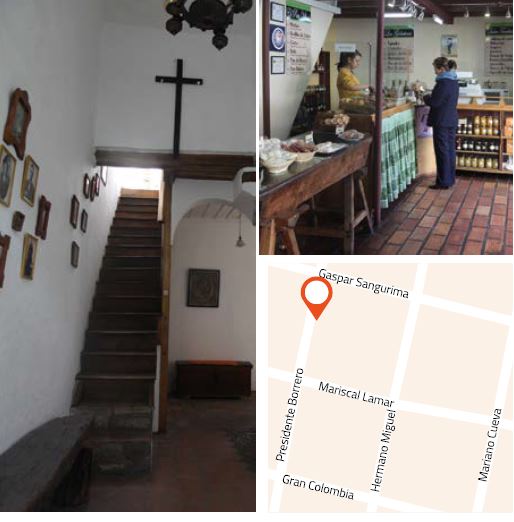

Sisters Of The Conception Museum

Although the sisters do not prepare bread for sale nowadays, they still make bread for their own use. The traditional recipes, which use natural ingredients, are maintained. The utensils employed are rudimentary, and one can still find large wooden troughs and wood-fired ovens in the convent’s kitchens

In the Sisters of the Conception Museum, a room has been arranged to exhibit photographs, attesting to the intense culinary labor of the nuns, who in addition to bread, prepare products such as agua de “pitimas” (a beverage made with valerian, carnation petals and rose petals) and quesadillas, the only products the nuns currently sell to the public through the Museum.

[color-box color=”gray”]Address: Hermano Miguel 6-33 and Juan Jaramillo

Hours: Monday to Friday from 09h00 and 18h30; Saturdays from 10h00 to 13h00

Telephone: 283-0625

Price of the visit: students $1.50 USD / university students and senior citizens $2.50 USD / national and foreign visitors $3.50[/color-box]

“El Pan De Las Villacís” Bakery

The bakery still functions in the almost 200-year-old family home, which preserves the characteristic charm of popular colonial-type buildings: tile roofs, adobe walls, internal patios and picturesque nooks decorated with family heirlooms. In one of the rooms at the back of the house, one finds the ancient wood-fired oven. Although nowadays it is no longer used every day, it still functions using traditional methods, which include lighting the wood to heat the oven and removing of ashes with a broom made of herbs.

The Villacises’ bread is known by all Cuencans for its exquisite flavor and as a healthful product, for the natural ingredients used in its preparation. Traditional recipes are used, which have not varied at all in spite of the passage of time. In this magical place, where time seems to have stood still, other products in addition to bread are prepared and sold, such as roasted coffee beans, cordials (sugar cane liquor with macerated fruits and herbs), kneaded cheese, fruit jams, handmade candy, milk caramel, etc.

[color-box color=”gray”]Address: Antonio Borrero 12-54 and Gaspar Sangurima

Telephone: 282-7914 / 099-303-2350

Hours: Monday to Saturday from 7h30 to 19h00

Price of the visit: A voluntary contribution is suggested.[/color-box]

Feature Photo Credit: John Keeble

The Mentidero Bakery

The Mentidero Bakery

One Response

I know how we’re going to be spending a lot of time! These tours sound wonderful